A week ago I wrote a blog

called Child

Murder about the homicide rates for children under 5 over the

past decade. It was written in quite a hurry, just before I went away on

holiday for Easter. When I wrote it I did not think that I would end up

devoting much more time on this topic, but after a bit more reading and

reflection I have found that I am dissatisfied with what I wrote and have a

number of unanswered questions I have yet to resolve. Instead of editing the

old piece, I have decided to let it stand and write a new blog.

The initial motivation for

this was to highlight the extreme discrepancy between the murder rates for the

trans identified demographic (a miniscule number) and that of Under 5s (a very

big number, significantly larger than the national average). I also wanted to

draw attention to the different political emphasis surrounding the two types of

murder. In the case of Zena Campbell, the Wellington Town Hall is lit up with

the blue and pink colours of the Trans Pride flag and Green MPs make righteous

statements at candlelit vigils. In the case of the death of

Moko Rangitoheriri, rallies

around the entire country demanding harsher sentences and ‘Justice for

Moko’. For the liberal left in New Zealand, taking part in public spectacles

highlighting the murder of trans people are an easy way to gain virtue credits

from a Wellington centred, Spinoff

reading, Green party voting middle class demographic. For the conservative right

in New Zealand, taking part in public spectacles highlighting the murder of

young children is an easy opportunity to push a number of Outrage Buttons: the

offenders are typically Maori, unemployed, unmarried and drink alcohol. They

get off on manslaughter charges, so we need to tighten up the justice system

and make sure they get long sentences for murder.

As I demonstrated in my earlier

blog the sections of the regressive left who push

the ‘trans people have higher murder rates’ narrative do not have facts on

their side. This is true not just for New Zealand, but for many other countries

including the UK, the US, and Canada. While I despise the racist,

beneficiary bashing, drug and alcohol scapegoating politics of the conservative

right, a statistical analysis of child murder rates over the past 20 – 30 years

has led me to realise that they really do have the facts on their side: the

murder rate for the Under 5 years old demographic increased markedly over the

period, and now far exceeds the murder rate for the general population. In this

piece I will focus mostly on the historical statistics comparing the murder

rate of the general population to that of the under 5 years old demographic. I

will conclude with some links to other studies and some broader remarks and

speculations, but my main intention here is just to highlight and explore the

most obviously relevant statistics. Without pretending to have the ‘answers’

that the left needs in order to articulate a strong and credible narrative

around these deaths that would serve a progressive (rather than conservative)

agenda, my hunch is that such a narrative would involve careful scrutiny of the

historical record.

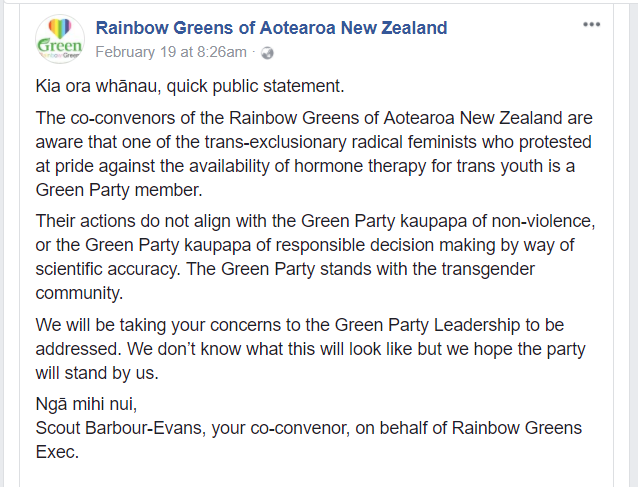

|

| Wellington City Council building lit up with the pink and blue colours of the Trans Pride flag to commemorate the death of Zena Campbell, March 2018 |

As something of an amateur

statistician, one thing I have learned is that searching for data on the

internet is nowhere near as easy as you would assume. A very simple table of

values showing the homicide rate per 100,000 people for New Zealand over the

past 60 odd years does

exist – but the data is not exactly the same as that found in

other sources (for example here or

here here or here

).There appear to be at least three different ways of measuring homicide:

sometimes it includes only murder, sometimes it includes manslaughter, and for

the even more broad ANZSOC (an Australian classification system) it includes attempts at murder. All three

definitions arrive at distinct sets of data, and this makes comparison with

rates of child murder quite difficult. The issue of ‘murder vs manslaughter’ is

not just a political hot potato, it is also a statistically important question

which potentially distorts and confuses the data. I have now looked at dozens

of academic and government studies alongside several New Zealand media articles

form the past decade, and there are clearly inconsistent standards being

applied. For example, if you look at the figures for child homicide in this

Stuff article from 2015 and compare it to those from a Police

report for the 2007 – 2014 period, the differences

are quite notable. Even though the graph from the Stuff

article is for the 0 -14 age bracket (which should give data

points equal to or higher than the 0 – 5 age bracket), some of the numbers are

higher (2009: 16 vs 12) and some of the numbers are lower (2007: 7 vs 10).

Despite considerable effort, I

could not find a single data source for a long historical period (1978 – 2015)

which I could use to compare the general population homicide rate with the

Under 5s rate. In the graphs which follow, I have used a variety of different

sources to cobble together the data needed for a long term view. If anyone out

there reading this can point to data sources which would provide a more robust

and consistent approach, please let me know. Till then I will simply note my

sources and acknowledge the limitations of this data.

SOURCES:

·

For the overall homicide rate for the 1949

– 2014 period, I have used this data set

provided by Statistics New Zealand and the Police Annual Report via the Te Ara

Encyclopedia website

·

For the average rate of under 5 homicide for

the 1978 – 1987 period (approximately 1.7 per 100,000) I have used ‘Homicide

in New Zealand: an increasing public health problem’ , an academic paper by Janet L. Fanslow, David

J. Chalmers and John D. Langley

·

For the period between 1986 and 2005, I

have used the five yearly averages stated in this

2008 MSD report

·

For the period between 2007 and 2014, I have

used the figures given in ‘Police

Statistics on Homicide Victims in New Zealand 2007 – 2014’

GRAPHS:

This graph shows the general population

murder rate for the entire period from 1949 to 2014. Through comparing the

numbers with other sources, it seems that this data is based on a narrow

(murder only, not manslaughter) definition of ‘homicide’. So it should be noted

that the rates are lower than they appear in other sources. Also, I have

supplemented the data for the years 2010 – 2014 from the Police report (using

murder stats only). The overlapping years (2008, 2009) give close but not

identical figures.

The most notable feature is

the gradual increase over the 1970s and early 1980s, followed by the sharp

increase during the peak years between 1985 and 1992. These years exactly

coincide with the neoliberal economic reforms of the fourth Labour government

and the subsequent effects of Ruth Richardson’s “Mother of all Budgets” in

1991. This correspondence between economic policy and the rise in crime is

given detailed and rigorous attention in the academic paper ‘Unemployment

and crime: New evidence for an old question’ (Papps

& Winkelmann 1999). The authors show that “there is some evidence of

significant effects of unemployment on crime, both for total crime and for some

subcategories of crime.”

Now for the comparison between

the general rate and the murder rate for under 5s. This graph uses the same

data from the time series above from 1978 onwards, and average rates for

different periods (visible as straight lines) for the under 5 subpopulation:

I was unable to find detailed

data for child homicide rates for all of the period except 2007 – 2014. The

numbers are small and very volatile, so it is worth graphing the murder rates

for individual years to get a sense of the variability of the data:

(According to this UNICEF report , the trend continued in 2015 with 11 murders

of under 5 year olds)

REMARKS

The first thing which I found

notable is the fact that high rates of child murder have a long history,

predating the murders of Chris and Cru Kahui in 2006 by decades. In the

Fanslow, Chalmers and Langley study of the 1978 – 1987 period noted above, the

overall murder rate for the period is calculated to be 1.6 per 100,000, little

different from the under 5 rate of about 1.7 per 100,000. My graph does not

properly reflect this very close match between the general rate and the child

rate, probably because of the data integrity issues described above. The

similarity between the overall murder rate and that of the under 5 demographic

is also commented on in the paper ‘Death

and serious injury from assault of children aged under 5 years in Aotearoa New

Zealand: A review of international literature and recent findings’ , a 2009 publication commissioned by the Office

of Children’s Commissioner:

Lawrence

cites Christoffel, Lui and Stamler (1981) who suggest that rates of death from

assault for children aged 1-4 years closely correlate with deaths at all ages. Similarly,

Fiala and LaFree (1988) argue that rates of violence for children and adults

are similar.

The references given refer to

both local and international studies: this is a worldwide phenomenon, not an

issue unique to New Zealand. A 2006

report by the Child Poverty Action Group draws

attention to the similarities between New Zealand and other colonial states

with marginalised indigenous populations:

If

child abuse were a “Maori” problem, we would expect to see it only within Maori

families. However, it occurs in communities the world over. Family violence,

sexual abuse of women and children, high levels of drug and alcohol abuse,

poverty and high levels of crime occur in other highly stressed communities.

Aboriginal communities, Native American communities in Canada and the US, and

African-American communities in the US are all grappling with these problems.

At present Australia is going through the same soul-searching as New Zealand in

respect of its Aboriginal people. The same arguments for and against government

intervention in Aboriginal families and communities are being aired, and the

same lack of consensus is evident. Child abuse is not, therefore, a function of

race or genetics, but rather a function of whatever those communities have in

common.

Yet something drastic, seismic

and horrendous happens in the period between the late 80s and early 90s. The

following table, also from the 2006 CPAG report, shows that this transformation

particularly affected the Maori community:

This very clear historical

shift is notably absent from all of the sensationalistic media attention devoted

to cases such as the Kahui twins and Moko. It is also largely absent from most

of the government reports on the issue, which tend to focus on data from narrow

time periods (for example, this

MSD study which limits itself to

2002 – 2006).

The second, and most

staggeringly awful thing about these graphs is the change that happens over the

first decade and a half of this century: while the general murder rate slowly

falls back to around 1 per 100,000, the rate for under fives increases. The average rate for the

period between 2007 and 2014 is around 2.6 per 100,000, more than double the rate for the general population. To be sure,

there are statistical reasons we need to keep in mind when looking at data sets

this small and volatile. A rigorous statistical study would need to address

these issues, and this sort of thing is way beyond the scope of this blog. The

thing that strikes me is that wretched and small minded conclusions insinuated

by sensationalistic media reports and conservative groups like the Sensible Sentencing

Trust are very clearly not the only viable forms of analysis. A politically

conscious and historical study of the data which related the tragic increases

in child murder to the devastation wrought by the neoliberal reforms of the ’84

– ’92 period would serve the interests of the left, not the right.

I’ll conclude this sketch of a

possible project with an hypothesis. The continuing high levels of child murder

throughout the period between 2005 and 2016 have another thing in common: the

perpetrators – almost always family members, and often mothers or fathers – are

typically young. These perpetrators would have been born sometime in the

period, say, between 1985 and 1997 or so. I haven’t looked at the stats yet but

I’m guessing the families they came from had all the frequently remarked upon

signs of deprivation and domestic violence. There’s a story to be told about

drugs and alcohol and single parent families for sure, but there is another

story too which recognises history: these little children probably never

watched the 6 O’Clock news when they were toddlers, but if they had done so

they would have heard the arrogant tones of Roger Douglas and the harsh metallic

voice of Ruth Richardson. Those voices never told them what to do or controlled

their actions directly, but the social shockwaves generated by their decisions

continue to kill.