|

| Renee Gerlich and Charlie Montague at Pride Parade, Auckland 2018 (Photo by Arthur Francisco)

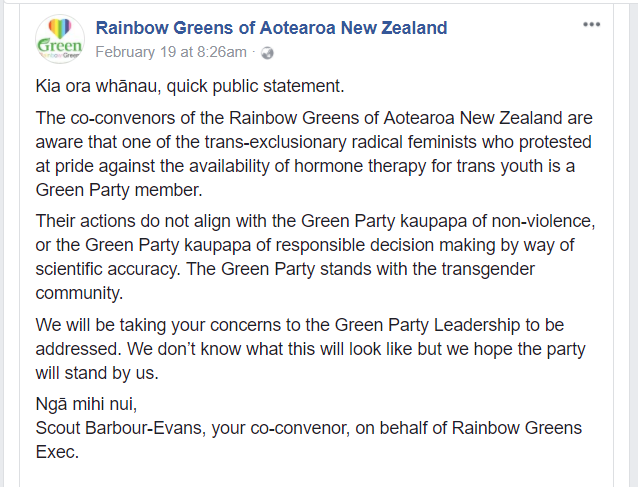

There was a similar post put up on the 'Young Greens' facebook page, which also also accused both Renee Gerlich and Charlie Montague of advocating funding cuts to LGBT youth groups 'Inside Out' and 'Rainbow Youth'. It has now been removed. Here is a screenshot:

In response to these accusations I wrote a letter to several Green party leaders. The following is a copy of that letter, with hyperlinks to articles backing up my claims:

To Whom It May Concern:

As a Green party supporter

with many friends and family members who have actively participated in the

party, I am very concerned and saddened by the Green party response to the

actions of Charlie Montague and Renee Gerlich at the recent Pride parade. On both the

‘Young Greens’ and ‘Rainbow Greens’ facebook pages there are posts which claim

that Montague and Gerlich advocate funding cuts to Inside Out and Rainbow Youth,

and that the protest banner they carried amounts to an attack on trans

identifying people. Both of these claims are false, and act to prohibit democratic

and critical debate about an important issue. Emotions often run high in these

debates, but that is all the more reason not to condone lies and smear tactics.

The protest banner carried by Montague and Gerlich read “Stop Giving Kids Sex Hormones – Protect Lesbian Youth”.

There is a real and substantive issue here about the physical side effects of

synthetic hormones and puberty blocking drugs such as Lupron. Worldwide the

numbers of children and youth who identify as transgender has skyrocketed only

very recently. There are therefore no long term scientific studies on the

potential side effects of these drugs. Yet existing studies on Hormone

replacement therapy for menopausal women, and the numerous severe side effects

on many people who have used puberty suppressants, are cause to take concerns

about this issue very seriously.

There are also numerous

studies which indicate that the vast majority of young people who experience gender

dysphoria during their youth go on to identify as gay or lesbian adults. In

countries such as the US and the UK, where the medicalised approach towards

gender non-conformity is well entrenched, there is a growing movement of ‘de-transitioners’

who have come to the realisation that the medical approach did not work for them. The majority of these people are young women who now identify as lesbian.

Clearly there are complex and

contentious political issues around these questions. The perspective held by many

trans-identifying people is very different from the feminist analysis of Charlie Montague and Renee Gerlich. So by all means encourage and support members

who wish to debate this important issue, clearly it deserves considered and

careful attention. What it does not need is lies and smear tactics.

Yours Sincerely,

Tim Leadbeater

|

Tuesday, 20 February 2018

Open Letter to the Green Party regarding Feminist protest action at Pride 2018

Saturday, 1 July 2017

Open Letter to the PPTA: Why is discussion about the medicalisation of gender off-limits?

I recently read an opinion piece in

the PPTA magazine by Lizzie Marvelly about the so called ‘bathroom battle’ over

transgender students and their access to toilets and facilities which match

their gender identities. Because I strongly disagreed with Marvelly’s

perspective on and framing of the issues involved in this discussion, I was

motivated to write a reply. Unfortunately the PPTA News editor did not accept

my piece, so I am reprinting it here because I doubt that any attempt to revise

my argument would satisfy the stringent conditions the PPTA places on debate

about transgender issues. I believe that the PPTA News editor has refused to publish my piece for ideological reasons. I will also argue that this refusal to allow debate amounts to a violation of one of the key stipulations in the PPTA's Code of Ethics.

Here is the article I submitted:

In a recent article published

through the PPTA, Lizzie Marvelly called the gender “bathroom battle” a “front

for intolerance”.

Marvelly is right to say that

schools should support and respect their LGBTQ+ students. Bigotry, intolerance

and bullying behaviour needs to be challenged and does not have any place in

our schools. I’m proud to work at a school that has a thriving ‘Rainbow Youth’

club, where many students take part in events such as the ‘pink shirt’ day

supporting tolerance and respect for gender non conforming people.

I also agree with Marvelly’s

contention that the bathroom battle is ‘proxy war’ with much deeper issues in

the background.

Marvelly’s portrayal of these

issues is problematic, though, for a number of reasons.

It may well be that Family First,

her target for criticism, is a conservative organisation with values

opposed to LGBTQ+ rights. Yet whatever the background motivations of Family

First, I struggle to understand how the concerns of female students can be so

flippantly thrown out with the bathwater as ‘bigotry’.

The recent case of a male

transgender student gaining access to female facilities at Marlborough Girl’s

College is a case in point. Laura, the student who spoke out last year against

the granting of this access, does not speak the language of bigotry. Laura’s

mother referred to the ‘vulnerability’ of teenage girls, and insisted that

males and females are ‘built differently’ and therefore need private spaces. Laura

said that she and her peers were not consulted, and talked about the ‘stressful

and embarrassing’ time girls can go through during puberty, and their increased

need for privacy from boys. She said that younger girls with a history of abuse

or trauma would be particularly sensitive and ‘triggered’ by the presence of

males inside their toilet facilities. In the AUT youtube video Marvelly

mentions, many of the women who spoke out against the wholesale replacement of

female only facilities voiced concerns based on their cultural values. None of

these were motivated by bigotry.

Another important background issue

is the debate surrounding the identification of transgender children. Many feminists are critical of the medicalised approach towards gender non-conforming

youth. They point to the gender stereotypes implicit in much of this

identification, and question the appropriateness and effectiveness of physical

transition. Lupron, the puberty blocking drug sometimes prescribed to

transgender identified children, has a number of very serious potential side effects. Taken in conjunction with synthetic hormones, Lupron causes permanent

sterilisation. Other potential effects include higher risks for chronic pain,

osteoporosis, depression and anxiety. There are unanswered questions about the

magnitude and extent of these risks because few scientific studies have been

carried out, and the fact that the population of medically transitioned people

has only very recently begun to increase dramatically. The long term effects of

drugs such as Lupron and the ongoing use of synthetic hormones are still

largely unknown - and this spells medical experimentation.

This medicalised approach towards

gender non-conformity goes hand-in-glove with the concept of a free-floating

‘gender identity’ which sometimes gets mixed up in the ‘wrong body’. Young

boys, for example, who like to play with dolls and wear pink are encouraged by

this ideology to identify as girls trapped in a boys’ body.

How does this ideology connect to

the bathroom battle? I am worried that promoting access to previously

sex-segregated spaces such as toilets based on ‘gender identity’ will

effectively normalise and validate this contentious ideology.

Do we really need to add to all the

pain and turmoil teenagers experience during puberty by suggesting the

possibility that their troubles are due to them being born in the ‘wrong’ body?

Is this even possible?

It seems clear that gender identity

ideology, not ‘bigotry’, is the bogeyman lurking in the shadows of this debate.

* *

The reply explaining why my piece

was refused I found deeply disturbing. Clearly my views on this issue are at

odds with the PPTA News editor, but I am certain that I am not the only PPTA

member out there with similar questions and concerns. Shutting down debate and

discussion about an issue which directly affects the wellbeing of some our most

vulnerable students seems to me clearly at odds with the PPTA Code of Ethics,

which demands that teachers “help all pupils to develop their potentialities

for personal growth”. How can we do that if we cannot even have a debate when

the views about how that growth can best be fostered are so hotly contested?

The really depressing reason behind

this is that the PPTA News editor is completely convinced that my views are

based on prejudice and intolerance:

A piece that

questions whether such a thing as being transgender is ‘even possible’ and

refers to gender diversity as ideology is not something we would run given we

have members who fit into these groups and work with these students. We have

democratically agreed guidelines affirming students with diverse genders and

sexualities and we don’t want to negate our work supporting all of our members.

I wonder what exactly ‘gender

diversity’ is, and why it is wrong to call it an ‘ideology’? I never used the

phrase in my piece, and I’m not sure of the answer to either of these

questions. What I am very clear about is what I object to and why. ‘Gender

identity ideology’ as I understand it involves the idea that people can be born

into the “wrong” body. There is typically some kind of appeal to the notion of

gendered brains or ‘essences’ which somehow get misplaced inside a body which does

not match up. The medicalised model of ‘gender affirmation’ via things like

synthetic hormones and surgery is the practical consequence of this idea,

together with the assumption that the body is more ‘plastic’ than the mind.

I don’t believe in gendered brains,

gender essences or the assumption that the body is more plastic than the mind.

I reject these ideas not out of ‘bigotry’ but because I believe that they do

not withstand scientific scrutiny, and also because I believe that these ideas

seriously undermine and negate critical feminist perspectives on gender.

I strongly believe that gay,

lesbian and gender non conforming youth should be supported and validated. I also

believe that there is absolutely nothing ‘wrong’ about the bodies of any of

these young people. I don’t believe that their bodies benefit from breast

binders, puberty blockers or synthetic hormones. I don’t believe that they

should be sterilised.

Clearly my beliefs at are at odds

with the PPTA News editor, and many others who embrace the medicalised gender

identity model. There is a debate to be had. Lots of people and organisations

have interests and agendas here – the drug companies and medical institutions

who profit from medicalising gender, parents of GNC children, feminist critics

and of course the children and youth who experience the real and acute pain of gender

dysphoria. I’m a parent of two young children and a teacher of teenagers. I have

an interest in this debate too as a human being and as a teacher who takes

seriously the stipulation in the PPTA Code of Ethics – let’s repeat it again:

Teachers should help all pupils to develop their potentialities for

personal growth

This is what the PPTA News editor

says about this important debate:

‘We also feel it

would be irresponsible to publish comments on side effects of specific

medications as we are not medical professionals.’

Well I’m not a medical professional

either. All I can do is read books and internet articles on this topic. I’m

sure there are many science teachers out there who read the PPTA News and also

know a huge amount more than I do about endocrinology, human biology and the

effects of puberty blockers. But of course we cannot even begin to discuss any

of this, because the people in charge of the PPTA News are not medical professionals.

We can talk about toilets and the

conservative bigotry of Family First, but we can’t talk about the physical

effects of breast binding. (I bring this up because the ‘Rainbow Youth’

facebook page recently featured an advertisement which celebrated these

devices - see also Renee Gerlich's piece for more on this topic). This is what a ‘top surgery’ specialist has to say about breast binders:

If you are

considering long-term chest binding, then there are some important things to

keep in mind. This following are the three biggest health consequences of chest

binding that you need to be aware of before you do begin.

Compressed Ribs

One of the biggest

health consequence of chest binding is compressed or broken ribs, which can

lead to further health problems. Unfortunately, you can fracture the ribs fairy

easily so you should avoid binding your chest using bandages or tapes, as these

can be unsafe.

Compressing your

chest too tightly or incorrectly can permanently damage small blood vessels.

This can cause blood flow problems and increase the risk of developing blood

clots. Over time, this can lead to inflamed ribs (costochondritis) and even a

heart attack due to decreased blood flow to the heart.

The following

are some symptoms you should look out for:

·

Loss of breath

·

Back pain throughout the back or shoulders

·

Increased pain or pressure with deep breaths

Collapsed Lungs

Since chest

binding can lead to fractured ribs, this can increase the risk of puncturing or

collapsing a lung. This happens when a broken rib punctures the lung, causing

serious health issues.

Once the lung is

punctured, it has a higher risk of collapsing because air can fill the spaces around

the lungs and chest.

Back Problems

If you bind your

chest too tightly then it can cause serious back issues by compressing the

spine, which is part of your central nervous system. The spine controls many

functions, and you need to be very careful when doing anything that may cause

damage.

Back pain from

chest binding can also be an indication that a lung has been injured. If the

pain is coming from the upper back or shoulder, consult with a doctor for

further examination to ensure proper lung health.

Fractured ribs,

damaged blood vessels, or punctured lungs can cause difficulties down the line

and may stop you from being able to move forward with surgery. Keeping these

issues in mind will allow you get the most out of using chest binding.

Discuss chest

binding with an expert to ensure that you get the best results, reduce the risk

of complications, and create optimal health for you.

If you are a PPTA member, please

don’t talk about any of this. We can’t debate this because we are not medical

professionals. It’s much nicer and easier to just get Lizzie Marvelly in to

talk about toilets. That way we don’t have to deal with any of the hard

questions. Please don’t worry too much about the stipulation in the PPTA Code

of Ethics – let’s repeat it again just for good measure:

Teachers should help all pupils to develop

their potentialities for personal growth

Don’t worry about Lupron either.

You’re probably not a ‘medical professional’, so you shouldn’t even be trying

to read or understand the scientific literature on this topic. Please ignore

and do not dare to discuss with the PPTA facts such as:

Unproven: Lupron

Depot is unproven and not medically necessary for puberty suppression in

patients with gender identity disorder due to the lack of long-term safety

data. Statistically robust randomized controlled trials are needed to address

the issue of whether the benefits outweigh the substantial inherent clinical

risk in its use.

Of course it could be true that for

some gender dysphoric teens, the medical treatment model might be the only

thing that works for them. This is complex and difficult territory, and I am

sure that the PPTA News Editor would not encourage any debate around the issues

involved. We should not consider, talk about or debate the surveys which

indicate that about 80% of gender dysphoric youth desist from transgender

identification by the time they become adults. You should not read this article which scrutinises the debate around this statistical claim, and concludes:

Every study that

has been conducted on this has found the same thing. At the moment there is

strong evidence that even many children with rather severe gender dysphoria

will, in the long run, shed it and come to feel comfortable with the bodies

they were born with. The critiques of the desistance literature presented by

Tannehill, Serano, Olson and Durwood, and others don’t come close to debunking

what is a small but rather solid, strikingly consistent body of research.

Well, I see that I have gone way

over the 250 word limit for letters to the PPTA News, and for obvious reasons I

know you will not even consider publishing this anyway. It’s a shame that this

discussion has to be limited to blogs. If any PPTA members are actually reading

this, I would encourage them to read some of the recent pieces by Renee Gerlich on this issue. I would also encourage them to contemplate the meaning and moral

force of the stipulation in the PPTA Code of Ethics, which I will repeat once

again in conclusion:

Teachers should help all pupils to develop their potentialities for

personal growth

Monday, 27 February 2017

The Case Against Gender: a review of Sheila Jeffreys’ Gender Hurts

- Jeffreys, Sheila. (2014). Gender Hurts, London and New York: Routledge

- Hausman, Bernice L. (1995). Changing Sex: Transexuality, Technology and the Idea of Gender, Durham and London: Duke University Press

I shall postpone necessary preliminary

remarks and dive head-first into the juicy outrageous bits. Jeffreys pulls no

punches, and combines academic analysis with shocking and uncomfortable

anecdotes and images. There are no ‘trigger warnings’, and her robust,

matter-of-fact style will appear shocking to some readers. Under the section

heading ‘Surgery for male-bodied transgenders’, we learn of the difficulties

experienced by people with surgically constructed vaginas:

In one case […]

the skin of the scrotum that had been used in the constructed vagina had not

had electrolysis to remove the pubic hair and the hair grew inside the vagina:

‘One day I was making love and something didn’t feel right. There was this

little ball of hair like a Brillo pad in my vagina.’ A surgeon pulled the hair

out of him but warned it would continually grow back[i].

Gender

Hurts devotes an entire chapter to the experiences of women married to men

who transgender in middle age. Typically, these are heterosexual men with a

fetish for cross-dressing. They tend to embrace stereotypical notions of

femininity, and their practices place great strain on their wives. Jeffreys

describes the experience of Helen Boyd, a women with critical sensibilities who

‘never knew exactly what feeling like a woman was supposed to mean and rejected

femininity as socially constructed and constricting’:

…her husband

told her he did know what it was to feel like a woman, and it was certainly not

what she had ever felt. She explains: “The more I encouraged him to find an

identity that felt comfortable and natural to him, the more unnatural he seemed

to me. His manners changed, as did the way he used his hands. He flipped his

hair and started using a new voice.” She hoped his behaviour was just a “phase”

because “I felt as if I were living with Britney Spears. It was like sleeping

with the enemy[ii].”

Another chapter is devoted to the

issue of women’s spaces, and the morally aggressive politics of the transgender

lobby to gain male access to these spaces. The Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival,

a women’s only event which has been running since 1976, has been repeatedly

targeted by transgender activists. In 2010 the tactics used became

‘particularly violent and aggressive’:

Camp Trans […]

“vandalised the festival and threatened festival goers”. A flyer being

distributed by the activists showed a rather extraordinary degree of woman

hating: “A hot load from my monstrous tranny-cock embodies womanhood more than

the pieces of menstrual [sic] art

your transphobic cunts could ever hope to create[iii]”.

Taken together these three examples

sum up Jeffreys’ case against the politics and ideology of transgenderism. She

argues that this ideology and its associated practices harm trans people, women

and the feminist movement. Gender non conforming children are encouraged to

identify as ‘trans’ and risk major health consequences, and gay and lesbian people

also suffer. Her arguments are based

around an historical account of transgenderism as a socially constructed

phenomenon which grew out of medical practices relating to intersex people and

an associated discourse which created the concept of ‘gender identity’. It is

this historical account which I will focus on and elaborate, but before I do

this I will say a few words about the political context of Gender Hurts and some of the critical comments made about this

book.

The political battle between

radical feminists and transgender advocates is heated and Jeffreys’ text is

without doubt a weapon, a polemic directed straight at both the heart and mind

of the reader. The uncompromising use of ‘pronouns of origin’ instead of those preferred by transgender people, the claim that male power is the driving

force behind the politics of transgenderism and the insistence that women

should create and protect female only spaces – these tenets are all articulated

in both an academic and deeply personal register. No wonder then that Gender Hurts provoked a vitriolic

response from offended liberals, who denounced it as a politically reactionary exercise in

transphobic hate speech. Most of the reviews I read barely engaged with the

arguments made in the text, and tended to cast aspersions upon the scholarly

and moral integrity of the book instead of explaining why they thought

Jeffreys’ ideas and concerns were wrong and unwarranted. Tim R. Johnston, for

example, states that:

Jeffreys relies on a very small, controversial,

and often outdated set of texts and evidence to support her arguments. She does

not acknowledge the controversial or contested nature of this evidence, nor

does she entertain significant and established evidence that is critical of her

position. Second, the tone of the book is extremely disrespectful, and there

are several places where Jeffreys engages in significant misrepresentations of

transgender people, their allies, and research. These problems call into

question not only the book's academic integrity, but also Jeffreys's scholarly

objectivity and rigor.

In a review which is best described as apoplectic and

somewhat unhinged, ‘Overland’ reviewer Lia

Incognita simply refuses to engage with any of Jeffreys’ arguments on moral

grounds. Because Gender Hurts commits

the cardinal sin of not accepting the truth of the statement ‘transwomen are

women’, it is simply impossible that any of the arguments have any merit whatsoever.

The closest she gets to engaging with the text is through quoting Judith Butler, who very clearly has not read the book herself:

“If she makes use of social construction as a theory to support

her view, she very badly misunderstands its terms. In her view, a trans

person is ‘constructed’ by a medical discourse and therefore is the victim of a

social construct. But this idea of social constructs does not acknowledge

that all of us, as bodies, are in the active position of figuring out how to

live with and against the constructions – or norms – that help to form

us. We form ourselves within the vocabularies that we did not choose, and

sometimes we have to reject those vocabularies, or actively develop new ones.

[...]

One problem with that view of social construction is that it

suggests that what trans people feel about what their gender is, and should be,

is itself ‘constructed’ and, therefore, not real. And then the feminist

police comes along to expose the construction and dispute a trans person’s

sense of their lived reality. I oppose this use of social construction

absolutely, and consider it to be a false, misleading, and oppressive use of

the theory.”

In order to clarify my thoughts on these objections to

Gender Hurts, I carefully examined

the social construction arguments made by Jeffreys’ and the texts she uses to

develop her case. The most important book she refers to is Bernice L. Hausman’s

Changing Sex: Transsexualism, Technology,

and the Idea of Gender. I think Butler seriously misrepresents Jeffreys’ account

of social construction, and I shall explain why as I outline the most important

elements of the account.

Jeffreys argues that it is possible to articulate a

social construction account of transgenderism along similar lines to that of

homosexuality as famously described by Michel Foucault. Just as scientific

theories and medical descriptions wove themselves into nineteenth century

social relations to create an essentialised and naturalised category of persons

(homosexuals), the twentieth century contains a distinct yet parallel story

concerning the creation of transgenderism. The social identities created

through these discursive processes are shaped by the over-arching imperatives

of a patriarchal system of male dominance and heteronormativity:

The creation of the

transgender role can be seen as a way of separating off unacceptable gender

behaviour which might threaten the system of male domination and female

subordination, from correct gender behaviour, which is seen as suitable for

persons of a particular biological sex. In the case of homosexuality, the

effect is to shore up the idea of exclusive and natural heterosexuality; and,

in the case of transgenderism, the naturalness of sex roles[iv].

Unlike homosexuality, transgenderism required the

existence of particular types of specialised medical technology. Developments

in endocrinology (the field of medicine relating to hormones and hormone

therapy), anaesthetics and plastic surgery occurred in the first half of the

twentieth century. These developments influenced the treatment of intersex

people, who were now subject to medical procedures to ‘correct’ their ambiguous

sex. Whereas it is most certainly appropriate to label intersex infants as ‘victims’

of medical technology, it is not at all true that transgender people were

similarly passive recipients of medical treatment. Jeffreys is most definitely

not guilty of the sin of denying ‘agency’ to transgender people. It is this

very agency which forms a crucial plank in the social construction account:

Hausman explains

that when there was public knowledge about medical advances and technological

capabilities individuals could then name themselves as ‘the’ appropriate

subjects of particular medical interventions, and thereby participate in the

construction of themselves as patients[v].

Both Hausman and Jeffreys describe the ideological processes

and changes which accompanied this construction of a ‘born in the wrong body’

subject. Hausman provides us with an acute and insightful view into the

pre-requisite assumptions required for sex change medical procedures:

To advocate

hormonal and surgical sex change as a therapeutic tool for those whose ‘gender

identifications’ are at odds with their anatomical sex, it is necessary to

believe that physiological interventions have predictable psychological

effects. In order to do this, evidence of the unpredictable psychological

effects of plastic surgery must be marginalised, understood as aberrant

(neurotic or psychotic) reactions, or controllable through patient selection –

and certainly not the norm. It is necessary to believe, further, that patient

‘happiness’ is a recognisable and realizable goal for surgeries that have no

physiological indication. And, in addition, it is necessary to acknowledge a

certain autonomy of the psychological realm such that the psyche is understood

as the realm of stability and certainty, while the body is deemed mutable[vi].

It is worth pausing here to take in

and consider Hausman’s perspective. To question the fact that people seek

medical procedures which help ‘align’ their anatomy with their gender identity

is currently viewed as tantamount to a fascist hate crime. Yet clearly there

are a host of quite unique and questionable metaphysical ideas which make such

facts possible. Usually people seek medical treatment for physical ailments,

and psychological treatment for mental distress. There are of course drug

treatments for people with severe mental illnesses, but these are informed by a

lively debate about the relative merits of different treatment approaches.

Medicalisation of psychiatric conditions is a political subject of debate when

it comes to things like drug treatments for depression, but such debate is a

moral taboo when it comes to gender issues. Gender identity advocates insist

that there is absolutely nothing ‘pathological’ about seeking medical treatment

for gender dysphoria. This moral position very effectively silences any debates

about the nature and causes of gender related distress.

These metaphysical assumptions

which underlie the medicalised treatment model were facilitated by the

development of ‘gender’ and ‘gender identity’ as discursive entities which

became progressively removed from material biological reality. This process

started in the early twentieth century with the treatment of intersex infants,

and reached its peak in the 1950s and 1960s with the work of John Money, Joan

Hampson and John Hampson. Prior to the 1950s the word ‘gender’ was an obscure

grammatical term, and was not a part of everyday parlance. The phrase ‘gender

identity’ entered the world in 1964, in an academic paper written by a

psychologist[vii].

Jeffreys argues that this discursive development facilitated the normalisation

of the transgender subject:

Hausman argues that

the ‘production of the concept of gender in Western culture’ can be analysed.

All of the medical ‘interventions’ […] depended upon ‘the construction of a

rhetorical system that posits a prior, gendered self necessary to justify

surgical interventions[viii]’

Hausman’s account also casts the

dependence the other way around, so that medical practices and gender discourse

mutually support each other:

… the semiotic

shift from sex to gender, from body to mind, relied on the use of plastic

surgical technologies as treatments for impaired psychological functioning[ix].

Again it is worth pausing and taking stock of the

implications of Hausman’s view. She is not in any sense ‘discounting’ or ‘erasing’

the lived reality of people who come to think of themselves as born in the

wrong body. She is instead clarifying the historical conditions of possibility

for such beliefs to exist. These historical conditions involve both medical

technology and a very particular type of gender discourse. Both Jeffreys and

Hausman are severely critical of the view that transgender identities can be retrospectively located throughout history and across different cultures in

various types of ‘third genders’. Transgender identities are a specific product of the twentieth century.

Hausman describes how the discourse on gender shifted from a

social to a private and individualistic register. ‘Gender’ was conceptualised

as both a set of social roles and stereotypes, and as a private essence inside

people which develops over time. Because intersex people frequently experienced

great suffering when their internal sense of gender did not match their

assigned social role, the medical approach was to ‘fix’ the anatomy to line up

gender identity with sex. Psychologists and sexologists increasingly emphasised

the notion of gender identity, rather than gender roles, and came to view

gender identity as something that was fairly rigidly ‘imprinted’ on the mind in

early childhood. Hausman explains the problematic consequences of this ‘imprinting’

model:

To suggest that

socially constructed behaviours are imprinted,

that is, established irrevocably and without flexibility, is, however, to lend

tacit support to culturally hegemonic rules and expectations. The concept of

imprinted behaviour suggests the idea that while there is one correct pattern

(heterosexuality with its concomitant masculine or feminine gender role

expression), this pattern can be wrongly imprinted. Because the notion of

imprinting suggests irrevocably established behaviours, the only way to affect

(or ‘cure’) the anomalous imprint – so that the subject can engage in cultural

activities as a ‘normal’ person – is to alter some other aspect of the subject.

In the context of intersexuality, after gender role has been imprinted, the

subject’s genital morphology and hormonal makeup become targets for medical

intervention. The same holds true for transsexualism and it is in this

connection that transsexualism appropriated one of its strongest arguments for

surgical and hormonal sex change, as transsexuals are understood to be subjects

who for some reason develop the ‘wrong’ gender identity for their anatomical

sex[x].

Sheila Jeffreys observes that the majority of people who

argued for these sex change procedures were male, and argues that the male

character of the demand for access to medical treatment is a defining feature

of transgenderism. She traces the history of this demand, from famous early

cases in the 1950s such as Christine Jorgensen to the ‘pioneer’ efforts of

cross dresser Virginia Price in the 1960s and 1970s. Following the controversial studies of Blanchard and Bailey, she distinguishes between

homosexual men who transition and heterosexual men who are motivated by autogynephilia (an erotic fetish for dressing in women’s clothing). Jeffreys

argues that we should not accept the separation between gender identity and

sexuality as unproblematic, and that feminists should be wary of the motives of

men who transition.

Considering Butler’s criticism of Jeffreys’ view, it is true

that Jeffreys supports a sort of ‘feminist policing’. Women are justified,

according to Jeffreys, in rejecting the presence of male transgenders inside

spaces such as toilets and changing rooms, and a part of this justification has

to do with the prevalence of autogynephilia. Women are also justified to be

critical of the views put forward by male transgender ‘feminists’ such as Julia Serano. She recounts the experience of Serano who wrapped a lacy white curtain

around his eleven year old body like a dress, satisfying a deeply felt urge to

feel ‘feminine’. Noting that his experience is “unlikely to have been shared by

many females”, Jeffreys ruthlessly exposes Serano’s efforts to “reinvent ‘feminism’

to fit his erotic interests[xi]”.

What is at stake here is not the ‘reality’ of social constructions, but rather

the male power and patriarchal structuring of sexuality which informs the undenied reality of those same constructions.

* * *

Sheila Jeffreys’ forthright and

uncompromising feminist stance is tempered somewhat by her admission in the

introduction that most of the literature on the transgender phenomenon is

celebratory rather than critical, and that she had to read ‘against the grain’ in

order to develop her account. Relying in part on the burgeoning scene of radical feminist bloggers critical of the current political climate surrounding

transgender issues, Gender Hurts is

best viewed as hybrid of academic theory and political polemic. Coming in at

under 200 pages, it is a ‘monograph’ which left me dissatisfied, not because of

its critical sensibility but because of its brevity. There may well be holes in

Jeffreys’ arguments and shortcomings in her account, but Gender Hurts deserves considered recognition and engagement, not

abuse and dismissal.

[i] Jeffreys, Sheila. (2014). Gender Hurts, London and New York:

Routledge, p.70

[ii]

Ibid. p.93

[iii]

Ibid.p.168

[iv]

Ibid. p.17

[v]

Ibid. p.21

[vi]

Hausman, Bernice L. (1995). Changing Sex: Transexuality, Technology and

the Idea of Gender, Durham and London: Duke University Press, p.63

[vii]

Robert Stoller, ‘A Contribution to the Study of Gender Identity’, Journal of

the American Medical Association 45 (1964): 220 – 26

[viii]

Ibid. p.27

[ix]

Ibid. p68

[x]

Ibid. p.101

[xi]

Ibid. p. 50

Sunday, 26 February 2017

Transplaining Spin: Fact-checking the liberal reaction to Ask Me First

The Spinoff news site has recently published two

articles in response to the Family First ‘Ask Me First’ campaign. Laura,

a student, has expressed

concern about Marlborough Girls College's decision to allow a male transgender student use of

the female toilet facilities. Supported by her mother and the conservative

lobby group Family First, she appeared recently in a Family First video speaking

out against the school’s decision and the lack of consultation with students

and families. Both articles strongly condemn Laura's stance, and paint her actions as a part of a bullying transphobic campaign against a powerless and vulnerable trans student. They both claim that there are no safety concerns for the female students, whereas there are major safety concerns for the trans student.

Is it true that the safety concerns lie squarely on the side of the trans student, and that people who question this narrative are transphobic bullies? Is it true that the trans student is relatively powerless and deserves more moral consideration than students such as Laura?

Is it true that the safety concerns lie squarely on the side of the trans student, and that people who question this narrative are transphobic bullies? Is it true that the trans student is relatively powerless and deserves more moral consideration than students such as Laura?

The first Spinoff article, written by Television editor Alex Casey with a palpable sense of

delicious moral outrage, denies the claim that there was no consultation

process. She interviews transactivist Lexie Matheson, who paints a rosy picture

of ‘unity’ at the school, and claims that the ‘school consulted widely,

they consulted the community, they consulted the students and the student LGBT

groups, I was able to talk to most kids and see the students in her classroom.’

He goes on to categorically state:

Everybody was asked first. The school was fantastic in terms

of talking to the community, sending emails and newsletters out and talking to

anyone with concerns. Many people did came to me with concerns about how it

would affect them. The answer, of course, is that it doesn’t affect you at all.

This directly contradicts the account given by Laura and her

mother. From the recent

Herald article on February 22nd:

Laura's mother says the school's claims that it considered

the rights of all its students before making the decision are "really

incorrect".

"They have not respected the value of the girls'

vulnerability. They haven't respected their thoughts on the matter. There's

over 600 girls. They also have a right to have a voice.

"I think as a parent, we should've got together in the

school itself before it all happened. Why didn't they ask us what we wanted to

do?"

Laura adds that while she has nothing against the

transgender student involved in the stoush, she takes issue with the school's

lack of consideration of her views.

"[The school] never asked me my opinion. They never

respected my rights. Nobody asked me first."

So which version of events is true? Were the parents and

students asked about the decision to allow a male student to use the girls’

facilities? Was there a warm, loving glow of tolerance which enveloped the

entire school in support of the transgender student, Stephani Rose Muollo-Gray?

Were the only exceptions to this enlightened and harmonious community small pockets

of close-minded fundamentalist Christian bigots, hatefully opposed to

transgender bathroom rights?

If you read Muollo-Gray’s statement which accompanied his petition

to allow his use of female facilities from June last year, a very different

picture emerges. He states that he started off using the female toilets, but

was challenged by a teacher for doing this and subsequently had a series of

meetings with the principal about the issue. The principal had originally made

it a condition that Muollo-Gray should use the unisex toilets provided by the

school, but Muollo-Gray had no recollection of making this agreement. The

statement makes it very clear that there was a lengthy process of debate and

discussion, and that the school authorities were initially opposed to

Muollo-Gray’s demand:

Several other meetings occurred with very little progress.

They kept trying to tell me that I couldn’t use the girls’ bathrooms because it

was all about everyone’s comfort and safety, as though anyone was at risk from

me just trying to use the bathroom. The one idea that they kept using as an

excuse as to why I could only use the few gender neutral or male bathrooms in

the school was that it would make some students uncomfortable, and that they

would complain and parents would become involved.

The petition gained 6,889 supporters and the story was widely

reported in the local and national media. The school soon changed its

policy and Muollo-Gray was allowed to use the female facilities. There is no

evidence that I could find of any sort of consultation process or vote about

the issue. The most plausible story is that the school changed its policy

because of the media spotlight and the pressure of the lobby groups in support

of Muollo-Gray.

A second claim made by both of the articles is that

excluding Muollo-Gray from female facilities would compromise his safety at the

school.

Lexie Matheson states: “The primary concern is safety and

feeling validated and authentic in yourself. … There is new research

coming out that often young transgender women often have more bladder

infections than the general population because we hold on for too long. We wait

until there’s nobody around and then we go to the bathroom, and that’s really

unhealthy and really unsafe.”

In the second article, Scout Barbour Evans states that: “…the Youth ’12 report – a report on the wellbeing of transgender youth in Aotearoa – has shown that 53.5% of trans youth are worried for their own safety at school. 17.6% of them are bullied at school at least weekly, and 19.8% of trans young people had attempted suicide in the last year. These are really, really alarming statistics. …everyone is focused on this theoretical, abstract debate about whether or not transgender people should be allowed to pee outside of their own homes, while our transgender rangatahi are suffering in a real, tangible way. We know from seeing the Safe Schools and marriage equality plebiscite debacle in Australia that when this sort of bullying happens by media, the overall wellbeing of our LGBTQ rangatahi goes down.”

In the second article, Scout Barbour Evans states that: “…the Youth ’12 report – a report on the wellbeing of transgender youth in Aotearoa – has shown that 53.5% of trans youth are worried for their own safety at school. 17.6% of them are bullied at school at least weekly, and 19.8% of trans young people had attempted suicide in the last year. These are really, really alarming statistics. …everyone is focused on this theoretical, abstract debate about whether or not transgender people should be allowed to pee outside of their own homes, while our transgender rangatahi are suffering in a real, tangible way. We know from seeing the Safe Schools and marriage equality plebiscite debacle in Australia that when this sort of bullying happens by media, the overall wellbeing of our LGBTQ rangatahi goes down.”

Both Matheson and Barbour Evans speak very generally, but

appear to be saying that without access to female facilities, Muollo-Gray would

be at greater risk of suffering bladder infections, bullying or suicide. Again,

it’s very interesting to compare these claims with Muollo-Gray’s petition

statement:

That aside what I want to get across is how blatantly

transphobic the school has been against me and how upsetting this whole

situation has been. There is no need to worry about other students safety in

this situation. It is me who has been forced to stop using certain bathrooms;

interrupting my learning and my school day. This whole situation has ended in

me being told I can use the gender neutral bathrooms that are available, and that

the school is looking to add more. But right now there are only four, and these

are at the outskirts of the school. As a girl I want to and should be able to

use the girls bathrooms. Why spend money on making bathrooms for me to be

segregated and out of sight of others when I can just go in the girls’ bathroom

free of charge? In the end it will be taxpayers forking out for this schools

transphobia.

The sentence which refers to ‘segregation’ is quite

misleading, according to this

article several of the previously female only facilities had been

converted into unisex facilities. Yet Muollo-Gray’s explanation is still far

more honest and grounded in reality than either of the hysterical Spinoff accounts.

What is at stake here is hurt feelings, the inconvenience of having to walk a

bit further than other students to access the toilet and the horrendous

possibility that the taxpayer would have to fork out precious funds to make

more unisex toilets. The most central reason is very clearly Muollo-Gray’s

presumed right to feel ‘validated and authentic’. Being excluded from female

only spaces is threatening to his psychological sense of ‘gender identity’.

The second

Spinoff article is titled ‘Teaching love: How to support your children

through questions about gender identity’. Full of love for the gender

non-confriming and gender diverse children of Aoteroa, Barbour Evans’ love does

not extend to embrace those unhappy with gender identity ideology:

We’ve seen “Laura” prodded into complaining by her (IMHO)

overbearing, bullying mother who raised a child to believe that transgender

people are subhuman in some way. We haven’t heard anything from the student

herself – a teenage girl with feelings and rights who does not deserve this

bullying from her peers."

I don’t know Laura or her mother, but from watching the ‘Ask

Me First’ video, it certainly is not clear that either of them view transgender

people as being ‘subhuman’. Laura’s mother refers to the ‘vulnerability’ of

teenage girls, and insists that males and females are ‘built differently’ and

therefore need private spaces. Laura talks about the ‘stressful and

embarassing’ time girls go through during puberty, and their increased need for

privacy. She says that younger girls with a history of abuse or trauma would be

particularly sensitive and ‘triggered’ by the presence of a male inside toilet

facilities. Both Laura and her mother also express concern for the precedent

set by this example, as it opens up the possibility of males using ‘gender

identity’ access to female spaces for exploitative or abusive purposes.

None of these concerns require adherence to religious

beliefs. It may be that some fundamentalist Christian people share these concerns,

but that fact in itself does not invalidate them. Transactivists such as Barbour

Evans and Matheson will invariably focus upon the supposed prejudice involved

with the concern about potential abuse, and will insist that there is no

evidence of any trans person ever harming anyone at any time. Unfortunately

they are wrong

about this, and there is considerable evidence that transgender males

commit violence

against women at about the same frequency as the male population as a

whole. Making this observation, and raising the issue of male violence and the

need for female only spaces is not ‘transphobic’ any more than it is ‘man

hating’.

Perhaps the most strikingly false statement is the second

part of Barbour Evans quote above, the suggestion that Muollo-Gray’s voice has

been completely absent from this affair. Teenage students as a rule have very

little say over how their schools are run. There are token gestures such as

student representatives on Boards of Trustees, but the reality for most teenage

kids is that of more or less complete powerlessness. They are compelled to wear

uniforms, attend classes, meet various behaviour requirements and so on.

Muollo-Gray’s influence over decisions made by the Marlborough school has been

massive. The petition, the media exposure and the trans lobby combined to

effectively make him more powerful than the school principal.

Psychological distress is an elusive thing to measure, but

in this case the apparent harms suffered by Muollo-Gray’s gender identity were counted as being far more weighty and significant by the school than any of the discomforts or fears held by

students such as Laura. Questioning the liberal orthodoxies of liberal Spinoff-doctors is an unpopular activity, but there is a compelling feminist case for doing so.

[For another left/feminist take on the Ask Me First story, check out Renee Gerlich's piece]

Thursday, 26 January 2017

The Intersex Continuum

I’m currently reading Alice

Dreger’s book ‘Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex’ and trying to

clarify for myself a series of questions about sexual dimorphism and social

construction claims about biological sex. The book itself is excellent and

highly readable, and surely a valuable resource for anybody who is interested

in the history of how intersex people have been treated by society (and

specifically the medical establishment) over the course of the past two

centuries. Dreger is an advocate for intersex rights, and supports the rights

and humanity of intersex people. For these reasons I would recommend the book unhesitatingly

to anyone interested in this subject. My take on it here will be quite narrow

and critical however, because I don’t agree with the strong version of the ‘sex

as a social construction’ thesis which frames the historical narrative.

Dreger is an historian who does not

question the Michel Foucault / Judith Butler inspired poststructuralist model

of inquiry, and describes the history of medical definitions of sex through the

nineteenth and twentieth century without any reference to a universal, history

and culture independent account of ‘true’ sex. In a characteristic passage she

states:

So, if we want to sort, what should we employ as the necessary

and/or sufficient traits of malehood and femalehood? What makes a person male

or a female or a hermaphrodite? This is the problem. Today my own students,

college students in history classes, sometimes in exasperation ask these

questions of me at the end of a discussion of the history of sex, as if I am

holding the ‘real’ answer from them. ‘What really is the key to being male,

female, or other?’ But, as I tell them, … the answer necessarily changes with

time, with place, with technology, and with the many serious implications –

theoretical and practical, scientific and political – of any given answer. The

answer is, in a critical sense, historical – specific to time and place. There

is no ‘back of the book’ final answer to what must count for humans as ‘truly’

male, female, or hermaphroditic, even though the decisions we make about such

boundaries have important implications. Certainly we can observe some basic and

important patterns in the bodies we call ‘male’ and the bodies we call

‘female’. And the patterns we notice depend in part on the cognitive and

material tools available at a given moment. But the development of new tools

doesn’t get us closer and closer to some final, definite answer of what it is

to be ‘truly’ male, female or hermaphroditic. Instead it only alters the parameters

of possible answers. A hundred years ago we could not point to ‘genes’ in the

way we can today, but being able to point to genes doesn’t mean that we have

found the ultimate, necessary, for-all-time answer to what it means to be of a

certain sex[i].

The theoretical model is that of a continuum or spectrum, with

more male traits on one side and female traits on the other. In the middle is a

blurry bit which gets labelled ‘intersex’ or ‘hermaphroditic’ (I’ll use the 20th

century term ‘intersex’). Because the points which define boundaries between

male, intersex and female change over time according to changing medical

definitions and theories, ‘sex’ is a socially constructed form of categorisation.

To put things very crudely, the wider and more fluctuating the blurry middle

part is, the more arbitrary and less ‘real’ sex classes such as ‘male’ and

‘female’ are. There are at least three distinct claims which typically employ the

sex as continuum model as a fundamental premise:

1. Biological sex is socially

constructed

2. Biological sex is not real

3. Biological sex is mutable

and changeable

I'll come back to claim (2) at the end of this post, but for now I will restrict my focus to the question of the nature of the continuum.

Specifically, if we accept that sex can be thought of as a continuum, how big

and how ‘blurry’ is the intersex part in the middle?

The Frequency of

Intersex Conditions

Alice Dreger’s discussion of the

complexities and pitfalls of arriving at a firm and precise percentage are

worth recounting and careful consideration. Before she gives any statistical

estimate, Dreger lists a number of reasons why ‘it is almost impossible to

provide with any confidence an overall statistic for the frequency of sexually

ambiguous births[ii]’.

Specialist medical texts offer different frequency estimates, so we don’t know

which sources to trust. The samples upon which they are based might not be

representative of the entire human population. Sometimes very rare intersex

conditions cluster in particular geographic regions, so it is hard to work

these local variations into a global statistic. Environmental factors such as

hormone treatments complicate the picture further.

More fundamental considerations

include the question of what exactly counts as an intersex condition. Some

types of intersex conditions result in very clear anatomical ambiguity, whereas

other types are less severe or less obvious. Particular conditions may or may

not manifest themselves as cases of sexual ambiguity. Should we count all of

the people with all of the various conditions, or only the cases in which sex

is difficult to determine? Dreger’s account is also centred around the idea

that the category of ‘intersex’ is culturally and historically relative:

… such a

statistic [of intersex frequency] is always necessarily culture specific. It

varies with gene pool isolation and environmental influences. It also varies

according to what, in a given culture, counts as acceptable variations of

malehood or femalehood as opposed to forms considered sexually ambiguous. And

it varies according to what opportunities there are in a given culture for

doubts to surface and be articulated on record. […] Frequency is specific to particular

cultural spaces[iii].

Nevertheless Dreger does eventually

offer us a statistical estimate:

When I am

pressed for a rough statistic, I suggest that today, in the United States,

probably about one to three in every two thousand people are born with an

anatomical conformation not common to the so called typical male or female such

that their unusual anatomies can result in confusion and disagreement about

whether they should be considered female or male or something else. Anne

Fausto-Sterling, through recent research, estimates the incidence of intersexed

births to be in the range of 1 percent, although Fausto-Sterling warns that the

figure ‘should be taken as an order of magnitude estimate rather than a precise

count.’ (In other words, the number might be closer to one in a thousand.)[iv]

Although I appreciated the reasons

for Dreger’s reluctance to state an exact figure, I found this statement to be

very odd. Was it one in a thousand or one in a hundred? It looks like Dreger

might be inclined to a more conservative figure than Fausto-Sterling, but she

does not explain why.

It turns out that Anne Fausto-Sterling

is one of the authors of the only academic study which attempts to rigorously

answer this question:

We surveyed the medical literature from 1955 to the present for

studies of the frequency of deviation from the ideal male or female. We

conclude that this frequency may be as high as 2% of live births. The frequency

of individuals receiving corrective genital surgery, however, probably runs

between 1 and 2 per 1000 live births (0.1 – 0.2%)[v]

Again, there are two estimates: a

liberal figure of 2% and a conservative estimate which differs by an order of

magnitude – quite a big gap! In a paper written before this research was

carried out, Fausto-Sterling provides an even more ambitious frequency estimate,

together with an almost lyrical evocation of the ‘sex as a continuum’ thesis:

For some time medical investigators have recognized the concept of

the intersexual body. But the standard medical literature uses the term intersex as a catch-all for three major

subgroups with some mixture of male and female characteristics: the so-called

true hermaphrodites, whom I call herms, who possess one testis and one ovary

(the sperm- and egg-producing vessels, or gonads); the male

pseudohermaphrodites (the "merms"), who have testes and some aspects

of the female genitalia but no ovaries; and the female pseudohermaphrodites

(the "ferms"), who have ovaries and some aspects of the male

genitalia but lack testes. Each of those categories is in itself complex; the percentage

of male and female characteristics, for instance, can vary enormously among

members of the same subgroup. Moreover, the inner lives of the people in each

subgroup-- their special needs

and their problems, attractions and repulsions-- have gone unexplored by science. But

on the basis of what is known about them I

suggest that the three intersexes, herm, merm and ferm, deserve to be

considered additional sexes each in its own right. Indeed, I would argue

further that sex is a vast, infinitely malleable continuum that defies the

constraints of even five categories.

Not surprisingly, it is extremely difficult to estimate the

frequency of intersexuality, much less the frequency of each of the three

additional sexes: it is not the sort of information one volunteers on a job

application. The psychologist John Money

of Johns Hopkins University, a specialist in the study of congenital

sexual-organ defects, suggests intersexuals may constitute as many as 4 percent

of births[vi].

**

Although the four percent figure

has been shown to be unsupported by the available evidence, it is hard not to

conclude that Anne Fausto Sterling is quite keen on the idea that the

percentage of intersex people is a lot bigger than people would tend to expect.

Vast infinitely malleable continuums need room to blur boundaries and break

categories, hundredths are way better than thousandths for this purpose.

All of the intersex advocacy

organisations I have looked at use Fausto-Sterling’s figures, and the OII Australia site contains a detailed list of distinct conditions with respective percentages. The most up to date quoted figure seems to be 1.7%, taken from a book written by Fausto-Sterling in 2000, which bases its figures on exactly the

same academic source I quoted from above.

The OII Australia site also refers

to an academic paper critical of Fausto-Sterling’s frequency estimate by Dr. Leonard Sax. He argues that Fausto-Sterling’s definition of intersex as

including ‘anything that deviates from the Platonic ideal of male and female

bodies’ is far too broad. His definition of what counts as intersex leads to a

radically different frequency estimate:

‘The available data

support the conclusion that human sexuality is a dichotomy, not a continuum.

More than 99.98% of humans are either male or female. If the term intersex is

to retain any clinical meaning, the use of this term should be restricted to

those conditions in which chromosomal sex is inconsistent with phenotypic sex,

or in which the phenotype is not classifiable as either male or female. The

birth of an intersex child, far from being “a fairly common phenomenon,” is

actually a rare event, occurring in fewer than 2 out of every 10,000 births[vii].’

The OII Australia site argues

against Sax’s narrow conceptualisation, and favours a broad and inclusive

category which

“…encapsulates

a range of atypical physical or anatomical sex characteristics. These share in

common their non-conformance with medical and social sex and gender norms. This

non-conformance with stereotypical standards for male and female is why

intersex differences are medicalised in the first place and, while that remains

the case, it makes sense to us to include them in a definition of intersex.

The

difference between narrow and broad definitions in medicine is somewhat

ideological. The exclusion of some diagnoses that embody atypical sex

characteristics but not others seems, at least to us, to be irrational.

Intersex people do not share the same identities, but we share common ground in

the stigmatisation of our atypical sex characteristics.”

Clearly

there is a very important question here as to whether scientific distinctions

and definitions are purely ‘ideological’ or not. Also, the suggestion here that

stigmatisation itself might be a criteria for what counts as ‘intersex’ is

surely problematic: flat chested women and men with high pitched voices may

well face stigma, that doesn’t mean that they are ‘intersex’. Another

consideration is how ethical considerations intersect with scientific

questions. Intersex people face marginalisation and stigma both because they

have bodies which do not conform to biological norms and also because such

conditions are in fact unusual. If the level of ‘unusualness’ is reduced, this

would arguably lessen the sense of marginalisation and stigma. Should we base

our definition of ‘intersex’ on social justice considerations or scientific

theories?

Putting

these complex and contentious philosophical questions to one side, what types

of specific ‘moderate’ intersex conditions are we talking about here? Leonard

Sax rejects several of the various types of intersex condition identified by

Fausto-Sterling because they do not fit his scientific definition. By far the

biggest category he objects to is that of ‘Late Onset Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia’ (LOCAH). This single

category accounts for a massive 1.5% of Fausto-Sterling’s 1.7% figure. What is

this condition and what are its symptoms?

The broad category of Congenital Adrenal

Hyperplasia (CAH) is described by a popular internet medical site as:

…an inherited (genetic) condition causing swelling of the

adrenal glands. The condition is associated with a decrease in the blood level

of a hormone called cortisol and an increase in the level of male sex hormones

(androgens) in both sexes. Some people get a mild condition that produces no

symptoms. Others (mainly baby boys) develop a severe form that can be

life-threatening. Medical treatment to correct hormone levels is available.

Surgery to improve the appearance of unusual genitalia (in girls) is sometimes

considered.

Leonard

Sax accepts that the severe (and very rare) form of CAH is a genuine intersex

condition, but he denies that the milder version of LOCAH is an intersex

condition. To sum up his analysis and put it bluntly: all men who have LOCAH

are unambiguously male. Sometimes they experience balding. Many women who have LOCAH have no symptoms. Of

those that do, symptoms include excessive body hair, infrequent periods and

acne. A small percentage of women with LOCAH have a larger than average

clitoris. If you want details, refer to his article through the link above

(it’s technical but not that hard to understand). I checked out a couple of the

studies Sax refers to. Dreger is correct when she warns about radically

different estimates from academic sources – the papers referred to by Sax quote

a frequency of around 1 or 2 in 1000 for LOCAH, very different from the 1.5%

figure. I’m not an expert in medical science, so it is hard for me to understand

this massive discrepancy. The best explanation appears to be that there is a

fairly wide spectrum of conditions which include higher than average levels of

male hormones in females (androgens), including rare conditions like LOCAH but

also including much more common conditions such as Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS).

The

conclusion to be drawn from these observations is that there appears to be a

contemporary trend towards a much broader and more liberal definition of

intersex conditions. This trend is in conflict with a more conservative

scientific definition of intersex. Radically different frequency estimates are

a consequence of this ideological conflict.

The

fact that this sort of conflict exists is consistent with Alice Dreger’s over-arching

postmodern narrative. She convincingly describes how doctors and medical

specialists strived throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth century

for a very narrow definition of intersex. By defining males in terms of the

presence of testicular tissue, and females in terms of ovarian tissue, the

existence of ‘hermaphrodites’ was squeezed into an almost non-existent

category. People with ‘ovotestes’ are extremely rare (0.0012% according to

Fausto-Sterling), so by defining ‘hermaphroditism’ in this way, Victorian

sensibilities could be preserved. The desire to preserve a rigid sex binary was

linked to societal gender norms and fear of homosexuality. The existence of

intersex people was a threat to the social order which needed to be contained,

so narrow scientific definitions were sought after for reasons which were not

always purely scientific.

Searching

around the internet for alternative interpretations concerning intersex, I came

across this tumblr blog which includes the most broad and liberal conception of

‘intersex’ that I could find. The authors of the blog insist that medical

authorities should not have the sole right to determine who is and who is not

intersex, and that people with PCOS are definitely intersex if they want to

self define as intersex. Crucially, the question of whether someone is intersex

or not has more to do with identification than it does with any sort of medical

description. The ideological underpinning of this blog may well be indicative

of a new historical era. Dreger’s phrase for the Victorian approach towards

intersex people was ‘The Age of the Gonads’. This blog may well go down in

history as representative of ‘The Age of Trans’.

Is

sex really a ‘continuum’? Is sex ‘real’?

We

can think of sex as a continuum, with male traits at one extreme and female

traits at the other. All people will fall within the reach of two intersecting

normal curves, the left curve representing mostly males and the right curve representing

mostly females. The intersection in the middle is the group of intersex people.

The problem for this very abstract model is the fact that biological sex can be

conceptualised across a number of distinct axes. We could look at genetic factors

such as chromosones, gonadal tissue, secondary characteristics (such as body

hair), genital morphology, hormone levels or reproductive capacity. Every

factor would produce a different sort of graph. The huge complexity of intersex

conditions would defy any attempt to provide a realistic picture with such a simplistic

model.

Professor Daphna Joel refers to a ‘3 G’ model of sex which defines sex on the basis of

genetic, gonadal and genital factors. Using this model, 99% of all people fall

into one of two categories, male and female. Males have all of these physical

features: XY chromosones, testes, prostrate and seminal vesicles, penis and

scrotum. Females have all of these features: XX chromosones, ovaries, womb and

fallopian tubes, clitoris, vagina and labia. This model is described as ‘almost

perfect dimorphism’. Intersex conditions mean that we cannot say that sex is

absolutely dimorphic. Some conditions (such as those which involve ambiguous

genitalia) are cases of unusual intermediate phenomenon. Some conditions (such

as Complete Androgen Insensitivity) involve a set of mis-matching features (XY

chromosones and testes combined with female genitalia). Joel emphasises how

incredibly unusual this almost perfect dimorphism is: we can be 99% confident

for example that a baby born with a penis will have all the other features ‘matching’

(testes and XY chromosones). There are very few natural phenomenon with this

high degree of probabilistic uniformity.

I’m

going to conclude by quoting a passage from an academic paper by Caroline New,

who argues against the idea that intersex conditions support the notion that

sex is not ‘real’:

Postmodern

writers massively exaggerate intersexuality and misrepresent sexual attributes

as continuous rather than as distributed dimorphically, despite the variations

and overlaps on any one dimension.

Do these variations mean that sexual difference is not real? Once again

postmodern feminists have higher standards than anyone else for categorisation.

Hawkesworth maintains that females and males are not ‘natural kinds’ because

there is no set of properties possessed by every member of each of these groups

(1997). From a realist point of view,

‘natural kinds’ are so called because they tell us something about the causal

structures of the world. Causally important properties are contingently clustered,

but in such a way that the presence of some properties renders the presence of

others more likely – because there are common underlying properties that tend

to maintain the clusters of features (Keil, 1989:43). Biological kinds can

never meet the essentialist criteria postmodern thinkers implicitly require

(Boyd, 1992). Biology is messy and complex, and its regularities take the form

of tendencies rather than laws. In the case of sexual difference, these

tendencies are strong, ‘the genotypic and phenotypic division of bodies into

two sexes crosses species and millenia’ (Hull, forthcoming). Sexual difference,

then, is a ‘good’ abstraction. Pace deconstructionists, it brings together

characteristics that are internally connected, and the connections in question

are substantial, not merely formal (Danermark et al 2002).

[i]

Dreger, Alice D. ‘Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex’. Harvard

University Press,1998.

[ii]

Ibid, p.40

[iii]

Ibid, p.42

[iv]

Ibid, p.42

[v] [Melanie Blackless, Anthony Charuvastra, Amanda Derryck, Anne

Fausto-Sterling, Karl Lauzanne, Ellen Lee, 2000, How sexually dimorphic are we? Review and synthesis , in American Journal of Human Biology 04/2000;

12(2):151-166.]

[vi] Anne

Fausto-Sterling, 1993, The

Five Sexes, in The Sciences 33: 20-25.

[vii] Leonard Sax, 2002, How

common is intersex? a response to Anne Fausto-Sterling, in

Journal of Sex Research, 2002 Aug;39(3):174-8.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)