Labour Day does not attract a lot of attention in the

New Zealand of 2014. There are no major ceremonies or parades, and

very little media coverage or discussion about its history or

meaning. It pales in comparison to other public holidays such as

Anzac Day and Waitangi Day, both of which are commemorated with big

ceremonies and a large amount of media attention and debate. Yet all

three public holidays represent a connection to an important aspect

of New Zealand's history: our bicultural heritage (Waitangi Day), our

involvement in war (Anzac Day) and our Labour history (Labour Day).

For many New Zealanders of 1890, Labour Day was not yet

an official public holiday, but it nevertheless represented a

significant and highly valued historical connection. The labour

movement of the time was growing more and more powerful, and it

viewed the year 1890 as the fiftieth anniversary of Samuel Parnell's

fight for the 8 hour day. Thousands of people took part in

processions in all of the major centres, where speeches were followed

by a sort of carnival. Paul Corliss describes the Wellington 1890

Labour Day:

The day was more passionate and organised than Union

members have contemplated, let alone experienced, in the last several

decades. The joyous atmosphere had been created at a price and at

some industrial risk. The editorial report (29 October 1890) about

the day highlighted some of the attendant tensions that were about

the city when it noted that “the strike had alienated the sympathy

of the majority of employers ...”. It further recorded that many of

the business establishments were closed all day and a number shut in

the afternoon. The parade encompassed not just trade unionists and

activists but deliberately involved the wider community, was

organised to incorporate the labouring classes, their families and

friends, and did not separate out the industrial or workplace agenda

from the family and its political future. Recreation and enjoyment

were also a well planned and essential component of the message1.

The 'recreation and enjoyment' aspect was quite

important, and reflected the culture of the time:

Aswell as the usual lolly scrambles and merry-go-round

rides, “youths and maidens” played the alluringly named “kiss

in the ring” or danced to one of the several bands present. The

'clever' Royal Gymnasts twirled on the Roman rings and tumbled

through their acrobatic exercises2.

Sports and games were intertwined with a more serious

political message. Corliss describes the massive Dunedin Labour Day

'after party':

A huge crowd, variously reported as 8,000 to over 11,000 people,

attended their sports' day at the Caledonian Ground. […] A little

after 5 o'clock that evening, the skirl of preceding bagpipes

signalled the late arrival of a large mass of Amalgamated Society of

of Railway Servants' members from the railway workshops. The

apparently despised Railway Commisioners had refused them a holiday

to participate in the day. They had decided to collectively vent

their displeasure at 'the tyranny of the Commissioners” and were

supported by the large and listening crowd who gave forth with a loud

three cheers for the workers and a thunderous three groans for the

Commissioners and the Government. The net sum raised on the day was

some £247

and with characteristic southern generosity £200

of this sum was donated to the striking miners at Denniston on the

West Coast3.

These descriptions of 1890's

Labour Day invite us to consider several questions: Why was the 8

hour day struggle such a big deal? What was going on in New Zealand

at the time to make labour issues so important? If it was such a big

deal then in 1890, why is it now such an insignificant public

holiday? How and why did Labour Day decline?

Samuel Parnell and the 8

hour day

Samuel Parnell was a skilled

carpenter who emigrated to New Zealand on board the Duke of

Roxburgh in 1840. He was not happy working the 12 – 14 hour

days he was expected to work in England, and dissatisfied with the

meekness of the union, which refused to fight for shorter working

hours. On board the same ship Parnell met a shipping agent, George

Hunter, who needed a carpenter to build a store for goods in transit.

Parnell agreed to work for Hunter, but only on the condition that he

work eight hour days. Hunter was not happy about these terms, but

reluctantly accepted them – skilled carpenters were in short supply

in New Zealand at the time.

|

| Samuel Parnell |

This precedent that Parnell

set was more than just a negotiation between an employer in a hard

position and an individual who drove a hard bargain: Parnell actively

spread the word about his success, and advocated other workers to

follow his lead. Bert Roth describes Parnell's precedent and the

collective action he inspired:

Other employers tried to

impose the traditional long hours, but Parnell met incoming ships,

talked to the workmen and enlisted their support. A workers' meeting

in October 1840, held outside German Brown's Hotel on Lambton Quay,

is said to have resolved, …. to work 8 hours a day, from 8am to

5pm, anyone offending to be ducked into the harbour. The eight hour

working day thus became established in the Wellington settlement. ….

The last resistance was broken, according to Parnell, when labourers

who were building the road along the harbour to the Hutt Valley in

1841 downed tools because they were ordered to work longer hours.

They did not resume work until the eight hour day was conceded4.

In the 1890 Labour Day parade

in Wellington, the elderly Parnell led the procession and gave the

keynote speech. There was actually a fair amount of debate at the

time however about who the rightful 'Father of the Eight Hour Day'

actually was. Samuel Shaw led a protest movement of workers in

Dunedin in opposition to Captain Cargill, who expected them to work

'according to the good old Scotch rule' of ten hours per day. In

Auckland the painter William Griffin organised the Carpenters and

Joiners Society to insist on eight hour days, which set a strong

precedent in that region also. Without getting too deep into the

historical details, it is fairly clear that skilled workers such as

Parnell, Shaw and Griffin were successful in establishing the eight

hour day as a national custom throughout New Zealand during the 1840s

and 1850s. They were successful in establishing this custom partly

due to the fact that skilled labour was in short supply, so they had

a strong bargaining position with employers. It is very clear however

that the employers were only willing to accept the eight hour day

because they were forced to. Without the determined collective action

organised by Parnell and other skilled workers, the eight hour day

would surely not have been successfully established as a custom.

Although by the time of the

1880s the eight hour day was customary, it was not an official law

and it was never universally observed. Bert Roth observes that

Tradesmen and labourers did

enjoy an eight hour day, but many other workers were still required

to put in longer hours. The plight of shop assistants was notorious

[…] farmworkers were another group working long hours, as were

domestic servants, clerks and, more surprisingly, locomotive drivers

and other staff in the state-owned railways5.

It also needs to be noted that

many of these 8 hour day campaigners went on to become settlers and

landowners. We can be rightfully proud of the values Parnell and

others fought for, but we cannot pretend that these values were on

offer to the tagata whenua. The category Roth mentions above of

'domestic workers' would have included a huge number of women. So

although the 8 hour day struggle was an important victory, we have to

remember that it was a victory mainly for white male workers.

The

1880s, Unions and the Maritime Council Strike

The massively popular Labour

Day parades of 1890 also had a lot to do with the broader historical

background of the 1880s depression and the labour struggles

throughout that decade. More and more workers organised themselves

into unions, and the demand for an official and legally recognised 8

hour day became a central issue. These unions now extended into the

ranks of the unskilled and semi skilled workers, and cooperated with

each other to organise as a more effective political force. This

pattern of more and more vigorous union activity led to the formation

of the Maritime Council in Dunedin, where in late 1889 seamen,

watersiders and miners joined forces. The leader of this new union,

Captain Millar, was a staunch proponent of the 8 hour day who both

promoted and organised the Labour Day processions of 1890.

The sad part of this story now

needs to be told: the Maritime council organised a nationwide strike

in August 1890, but this was eventually defeated. As Bert Roth

explains, 'The strike was in its dying stages in late October but,

though the outcome was clear, the Labour Day demonstrations were a

resounding success.'. So the popularity of the Labour Day parade and

the strength of feeling behind the demand for the 8 hour day needs to

be seen in the context of this defeat. Having said this, surely any

strike which goes nationwide and lasts three months is a really

powerful and significant achievement, even if it does get defeated in

the end.

This mixture of union

militancy and a tendency to back down and compromise is reflected in

the diversity of the banners carried by workers in the Labour Day

parade. Turning again to Bert Roth to illustrate this:

The 1890 Labour Day marches

were a show of strength by the union movement, a signal to the

employers that, though defeated, labour was still a force to be

reckoned with. 'Might is Right has run its race,' read a Dunedin

building workers banner, 'Right is Might now takes its place. Now law

but vox populi.' A Christchurch Amalgamated Labour Union banner

stated boldly that 'Labour Omnia Vincit' (Labour Conquers All), but

these were not revolutionary marches clamouring for the overthrow of

the economic system. Wellington watersiders, whose union and jobs

were about to disappear (they were being replaced by scabs) carried a

banner with the clasped hands symbol and the motto 'Defence not

Defiance', while the equally doomed Lyttleton wharfies had a banner,

designed by a union member, which depicted a merchant and a labourer

shaking hands and the inscription 'Labour and Capital as they should

be6'.

This picture can be read in

two ways: we can either focus on the tendency of some workers to back

down and cooperate with employers, or we can focus on the more

militant sections of the working class who carried the strident and

uncompromising banners. Just like with the Maritime strike, the

banners of the more militant workers should still be seen as

inspiring, even if large sections of the working class did not share

their militancy.

The

Rise and Decline of Labour Day

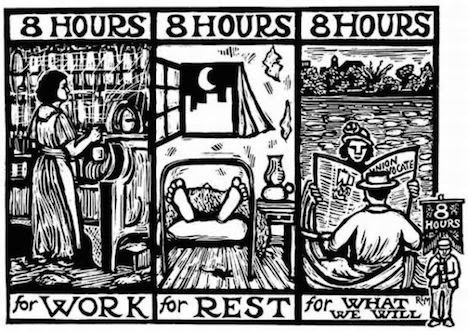

One feature of the Labour Day

parades which is quite significant is the nature of the floats,

banners and displays. Workers made models and banners depicting their

trades: seamen made model ships, the boilermakers carried a makeshift

furnace, bakers carried banners with pictures of their cakes and

bread and so on. So alongside banners demanding “Eight hours

labour, Eight hours recreation, Eight hours rest”, workers actually

displayed their pride about what they did in their jobs.

Unfortunately, this display of pride and dignity was displaced by

more commercial interests as the union movement receded, and business

owners manipulated the content and meaning of the floats and

displays.

After 1890, when most

unskilled and semiskilled unions collapsed, the annual processions

became again the domain of the tradesmen's societies, as they had

been in the 1880s. These societies vied with each other in displaying

their skills to the public, but they had to compete for attention

with visiting theatre groups and even circuses, which were allowed to

take part in the parades, and with business firms which quickly

realised the opportunity to promote their products. When the

breweries entered floats, the temperance societies insisted on their

right to provide counter-attractions denouncing the evils of the

drink traffic. As the processions were gradually drained of their

union content, the numbers of union marchers declined.

Labour Day became more and

more detached from its union heritage, and the focus was placed

mostly upon the afternoon sports and picnics: 'There were

merry-go-rounds and baby shows and all manner of entertainments for

young and old7.'

The fact that the 8 hour day custom, and the principled demand for

adequate leisure time which inspired it, came from a history of

worker's struggle was obscured by this depoliticised focus on

recreation. Politicians actively and skillfully manipulated the 8

hour day message into a subservient format: for example, the Liberal

politician Sir Robert Stout said this to the Wellington Labour Day

crowd in 1891: “..by insisting on the eight hour principle working

classes were fighting for their moral, mental and physical health and

would thus be doing a duty to themselves, to their families, and to

their employers8”.

Bert Roth concludes his

analysis of the decline of Labour Day:

The Labour Day celebrations

reflected the Lib-Lab ideology of a partnership between labour and

capital. When the Liberal-Labour coalition disintegrated, the Labour

Day marches also declined in popularity. They did not fit the

militant ideology of the Red Federation of Labour, which was in the

ascendancy in 1912 -13, and half-hearted attempts after the first

world war failed to rekindle enthusiasm. 'Labour Day', wrote the

Auckland Star in 1920, 'is a holiday to be enjoyed rather than

a day of aggressive demonstration as May Day is on the continent.'

Labour Day indeed became just another paid holiday, the proper time

to plant tomatoes9.

What can we learn from this

history?

Looking forward into 2015,

without any doubt the biggest and most ideologically significant

public holiday will be Anzac Day. The centenary of the Gallipoli

landings will be the occasion for an orgy of sentimentalised

'remembrance' and patriotism. Second place in this contest will

fortunately be awarded to Waitangi Day (there will probably be some

kind of repeat of the Herald's “protest free” edition, but this

will be fiercely and loudly countered by more progressive forces). In

terms of public spectacle and ideological prominence, Labour Day will

trail a distant third place.

Traditions and commemorations

are surely not monolithic, so although we are in a fairly depressing

period of history, I don't think we should succumb to depression. As

the Labour Day history shows, these sorts of traditions are

changeable, and their fortunes rise and fall according to the nature

and intensity of class struggle. The recent anti union 'tea break'

legislation is a good example of why the values and ideals which

motivated people like Samuel Parnell to fight for the 8 hour day are

just as relevant now as they were in the nineteenth century. Whether

or not Labour Day is resurrected, the struggle for time for us to do

as we please – free from the exploitative demands of the capitalist

economy – will continue to be an important aspect of political

struggle.

References

Corliss, Paul. 2008. “Samuel

Parnell – A Legacy: The 8 hour Day, Labour Day and Time Off”.

Purple Grouse Press.

Roth, Bert. 1991. “Labour

Day in New Zealand”. The Dunmore Press Limited

1Corliss

(2008)

2Ibid

3Ibid

4Roth

(1991)

5Ibid.

6Ibid.

7Ibid.

8Ibid.

ضواغط هواء خالى من الزيوت هو جهاز يضغط الهواء دون استخدام أي مواد زيتية داخل غرفة الضغط.

ReplyDeleteيُستخدم هذا النوع من الضواغط في التطبيقات التي تتطلب هواءً نظيفًا وخاليًا تمامًا من الزيوت، مثل:

المستشفيات

الصناعات الدوائية

مصانع الأغذية والمشروبات

الإلكترونيات الدقيقة

معامل التحاليل والمختبرات